World

A world-first in the Scottish Highlands

Mike MacEacheran

Mike MacEacheranAs rewilding accelerates around the world, the global movement’s first dedicated centre has opened in the Scottish Highlands.

If you cut down a rowan tree, should you ask permission from the sìthean, or fairies? Yes. Does a scarab-shaped woodland dor beetle squeak when you pick it up? Yes. Does each of the 18 letters in the Gaelic alphabet have a tree associated with it? Yes. Is the brown long-eared bat’s hearing so good it can make out the pitter-patter-pit-pat of an insect walking on a leaf? Yes. Can you eat bracken? Yes. Should you eat bracken? No.

Woodland trivia like this is the stock in trade of Michael Durrance of Trees for Life, an environmental charity in the Scottish Highlands, and the seasonal ecologist is an authority on the trees and insects, bats and brackens of the Dundreggan Estate, found west of Loch Ness in Glen Moriston’s denuded hills.

“People in the Highlands used to fry-up bracken fiddleheads, but it’s not good for you,” he said, as we followed a pathway that disappeared into silver birch and larch trees. “It’s full of carcinogens and can make you nauseous, dizzy and give you a bad headache. So do it at your peril.

While Durrance’s role is to educate visitors on the mysteries and unknowns of the Highlands’ landscapes during guided walks across the 10,000-acre estate, he is also a steward of the charity’s new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre, which opened in April 2023. Rewilding is the rehabilitation of ecosystems that can triumph and flourish without human interference, and the landmark attraction is both wildly ambitious and a bold statement of intent.

Mike MacEacheran

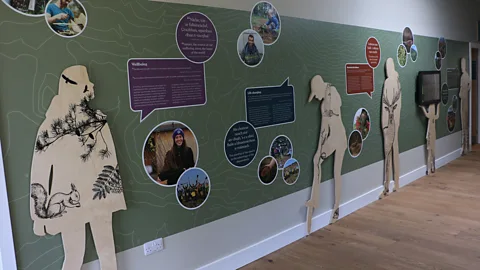

Mike MacEacheranThe origins of the visitor campus began five years ago when Trees for Life realised there was a major disconnect between people and landscape in the UK and set out to address the imbalance. The result is a free-to-access education centre and volunteer basecamp with training programmes, guided forest tours, seminars, nature workshops and activities, where the idea is to increase ecological literacy in the fightback against climate breakdown.

Trees for Life: What makes it regenerative?

Fittingly, the milestone centre, located on what was once part of a 14th-Century royal hunting ground, encourages experiences grounded in nature. To give visitors the sense of walking through a forest, the lighting and height shifts throughout the building.

On site is a research library, a bothy-style projection room, 40-bed accommodation complex for volunteers and researchers, plus classrooms and a natural history exhibition to help encourage rewilding in action. Meanwhile, outdoors are three educational walking trails, a dipping pond and tree nursery, where up to 100,000 saplings are grown each year to help revitalise the Caledonian forest. In places, Scots pine has been brought back to areas where it hadn’t grown for generations.

And since the charity’s beginnings more than 25 years ago, some two million carbon-sequestering trees have now been planted. On a map, these can be found in 44 sites that stretch across the Highlands, from Wester Ross to the Cairngorms.

“Ultimately, we’re providing a seed source for the natural forest of the future,” said Durrance, as we retraced our steps along the trail. “We’re giving nature a healing hand – and our work is already having an impact and making this corner of the world a better place.”

FLPA/Alamy

FLPA/AlamyTime-travel back to the Scotland of 6,000 years ago and the scene is of thriving Scots pine, rowan and oak and woodlands brimming with now-vanished lynx, beaver and wild boar. The forests were also settings for bears catching salmon and wolf packs hunting in meadows for deer, elk and auroch (a wild ox). Indeed, the Romans once called the forest-shielded uplands “The Great Wood of Caledon”.

But over the centuries, Scotland’s forest cover fell into sharp decline due to overgrazing and unrestricted logging, with huge swathes of the landscape pillaged for agriculture, ships and housing. By the time of the Highland Clearances of the 18th Century, near-industrial sheep farming dominated the landscape and forestry hit an all-time low. Another part of the history arrived in the form of two World Wars; with timber an essential for the war effort, the early- to mid-20thCentury did little to reverse the damage.

Even so, across Scotland these days there’s a feeling of healing. Rewilding is gaining momentum at pace across the country, and a new scenario of landscape-scale projects overseen by alliances of environmental stakeholders is evolving – and all with one purpose in mind: to make Scotland one of the world’s most influential rewilding nations.

At Dundreggan, the first thing a visitor notices – and it’s hard not to – is the birdsong. It’s a chorus of swallow, chaffinch, mistle thrush and hooded crow, a cadence of tweeters, chirpers, whistles and warblers. Sparrow hawk, golden eagle and osprey circle above these melodies, while orange-tip butterflies sweep across willow trees.

Mike MacEacheran

Mike MacEacheranAbove all, there is life in every nook and detail. There are invisible adders and slow worms in the tussocky woodland edges and strawberry spiders and giant juniper aphids in tiny spaces in the soil. In pitted moraine, sleek pine marten stake out their next meal and all around is a slew of alder and pine. Roe, red and sitka deer leave trail prints and, on higher ground, black grouse are lekking (a competitive spring courtship ritual). At the latest count, there are now 4,000 native plant and animal species on the estate, including feral pigs – or torc fiadhaich, in Gaelic – whose rootling exposes bare soil, giving tree seeds a chance to grow.

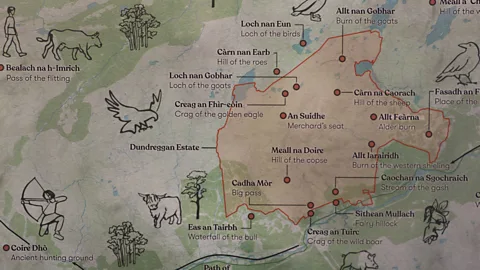

For centre director Laurelin Cummins-Fraser, Dundreggan is also preoccupied with re-educating visitors on the value of the cultural landscape. “Gaelic evolved in response to the countryside and many of its cultural roots are closely tied to the Caledonian forest,” she said, pointing out several nearby mountains, including Creag a’ Mhadaidh (the hill of the wolf) and Creag Bheithe (the hill of the birch). “It’s a chance to rediscover the landscape’s archive of Gaelic stories.”

The Highlands’ landscape is in transition elsewhere, too. Equally ambitious is the non-profit’s plans for the landscape-scale Affric Highlands project. As part of a 30-year initiative, Trees for Life and other stakeholders are restoring half a million acres of native woodlands from Loch Ness to the country’s west coast, encompassing Glens Cannich, Affric, Moriston and Shiel, in a joined-up approach to boost habitat connectivity and increase species diversity.

Mike MacEacheran

Mike MacEacheranIn similar terms, another proposition is Cairngorms Connect. Concentrated on a 232-square-mile subarctic plateau in Cairngorms National Park, the multi-landowner enterprise has embarked on a 200-year plan to breathe life back into the pine-wrapped glens. There are so many stories to tell, but one in particular stands out: in recent months, wildcats have been introduced back into the Highlands for the first time in more than a century.

CARBON COUNT

The travel emissions it took to report this story were 0.09 metric tons of CO2e

What Scotland is seeing is a tumble and crash of ideas. And the lesson to emerge is that, though ecological literacy is growing in society, the environment will only prosper on a landscape-sized scale if everyone – from farmers to fishermen to deer stalkers to land managers – all realise the benefits of rewilding and join the fight.

Given time, a place like Dundreggan may one day return to its past glory. Like so many other countries, Scotland is wrestling with climate breakdown, but a world of possibilities is beginning to reveal itself in the Highlands and nature is showing how it can once again find its way. In glens where predators creep and where ancient pine, birch and rowan once again stalk the land.

Thoughtful Travel is a BBC Travel series that helps people explore places responsibly and sustainably, all while making them better through regenerative and responsible travel.