Sports

Olympics tattoos have become mandatory for athletes but they mean much more than you think

Chris Jacobs brought home two gold and one silver medal from the 1988 Olympics but another significant souvenir. The swimmer’s route back home to Texas from South Korea went via Hawaii, where he decided to add to the tattoo on his hip, the logo of his college team the Texas Longhorns. In between the horns went the Olympic rings, the first known instance of a now-ubiquitous tattoo.

Many others have followed. At first it was swimmers, Americans mostly, with traditional placement in an area covered by trunks: hips or buttocks. But logo tattoos are now displayed proudly by athletes from all over the world. Years later Jacobs even had another set added on the inside of his bicep.

For Olympians, getting one is as much a rite of passage as the sacred moment in the village when they receive their branded condoms.

Canadian swimmer Victor Davis was Jacobs’ inspiration. He had a maple leaf visible on his left breast at Los Angeles 1984, so small it could be mistaken for a third nipple. It was rare to see a visible tattoo at the time and Jacobs decided to ape it when decompressing in Hawaii four years later.

“It was just an opportunity to relax and let the goosebumps subside,” he says. “The Olympics had been such an intense experience, something completely different, unlike anything I had ever been through before and very surreal.”

If Jacobs is the Bill Haley of the rings tattoo, Michael Phelps and Ryan Lochte are its Lennon and McCartney. Lochte’s coloured rings on his inside right bicep became a familiar sight when he and Phelps (right hip, smaller, generally partially obscured) were on their way to 40 medals in their Olympic pomp.

“Like so many other aspects of swimming the moment Michael Phelps got involved it moved front and centre,” says Jacobs. “I know a bunch of swimmers had it before him and Ryan Lochte, but Phelps made swimming a popular sport in America and all around the world.”

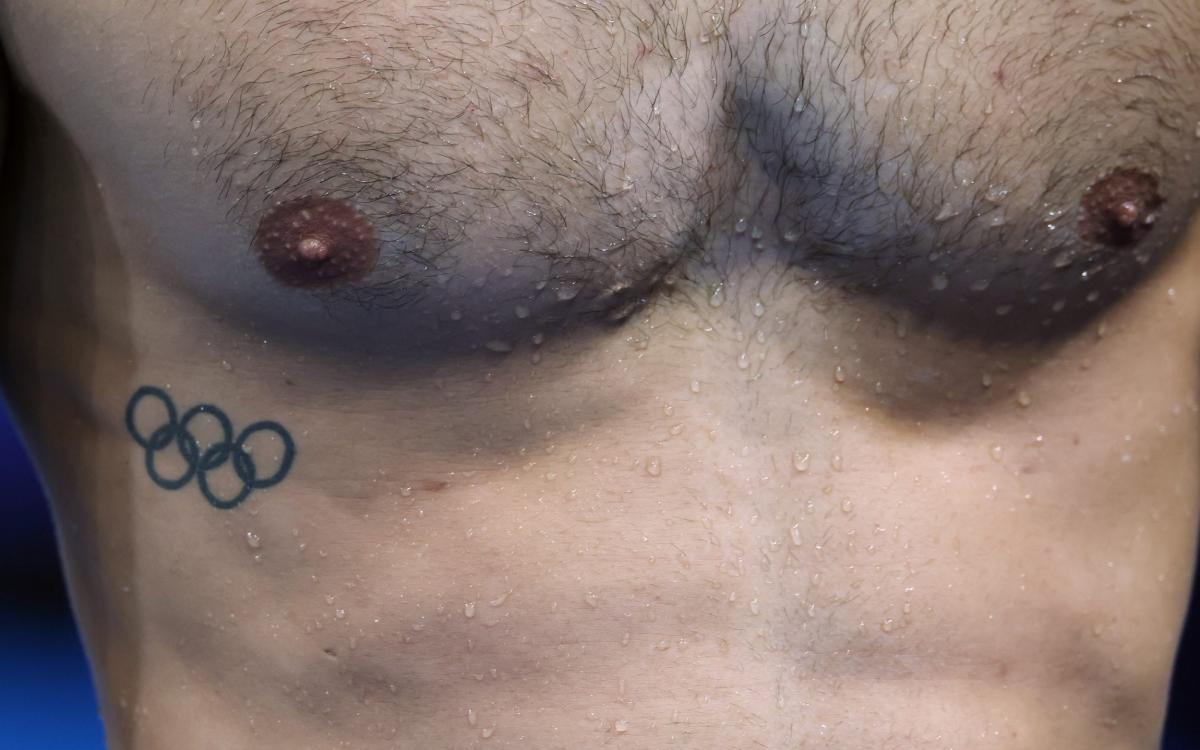

Now the tattoo is so common it would be quicker to name the athletes who do not have one. Among the British contingent are Tom Daley (right bicep), Adam Peaty (left bicep), Mark Foster (left breast), Rebecca Adlington (lower back), gymnast Beckie Downie (right ankle), and canoeist Adam Burgess (right forearm). The boat-based Olympic village in Tahiti at this Games has a tattoo parlour on board for any surfers wishing to join the ranks.

But just as some say it’s not the Olympics until the athletics starts, it’s not a phenomenon until the Americans get involved. They take their rings tattoos seriously. Woe betide the fan or volunteer who wants to commemorate the Games, the American view is they are only permitted if you have competed. Some hardliners believe only a gold medal is sufficient.

It is understandable that those who strive so hard to clinch a squad berth are scornful of anyone taking a shortcut to reflected glory. A few years ago there was a thread in the Olympics Subreddit detailing examples of non-Olympian men getting rings tattoos to help them pick up women.

Some opt for ink as soon as their place is confirmed, which can be risky should injury intervene. Most prefer to wait until their race is run. American boxer Jaira Gonzalez earned the ire of her father by having the rings and the Eiffel Tower tattooed before the Games had begun. “My dad, I love that man. He is always super hard on me,” she said. “He was kind of mad when I got the tattoos with the rings and said, ‘You’re not an Olympian yet. You don’t have the gold medal yet.’ But I’m like, ‘What are you talking about?’ I can see where he was coming from now, but it’s on my skin now. I can’t do anything about it.”

Some pay for their tattoos with more than fate-tempting red faces. In 2016 British Paralympic champion Josef Craig was disqualified at the IPC European Swimming Championships because of the rings over his heart which allegedly “breached advertising regulations”.

Clearly tattoos have become more common but the spread of the rings has a lot to do with good old-fashioned peer pressure. They will be everywhere in the village, and that gives unmarked athletes an idea. “It’s one of the things you see all the cooler Olympians having,” said archer Brady Ellison in 2016.

If you also saw the cooler Olympians, jumping off a building or firing arrows, would you do that too Brady? Don’t answer that.

But there is a nobler aim in commemorating an Olympics appearance. A tattoo is a testament to sacrifice, one that does not have to live in a safe like a medal. “It’s an interesting reminder of a really meaningful time in my life,” says Jacobs. “It helps me to remember that I can work through any challenges, and generally hard work and diligence really does work. Focus and hard work gets you to where you want to go, or very close to it.”

Of course there is one feeling many people share about their youthful tattoos, a wish they had never got them. Not Jacobs, though. “I don’t regret it,” he says, and the version on his bicep serves another purpose: “It keeps me in the gym. I can’t have it shrink into nothingness.”